Media Reported Trauma – 10 Tips for supporting young people

by Collett Smart [This article is regularly updated]

Weekly news reports of traumatic images and stories of pain and destruction such as; natural disasters (bushfires, floods, volcanoes and earthquakes), the coronavirus, terrorist attacks, threats of war and shootings can cause great concern in children. Adults can sometimes assume that teens are coping with the overload of media reported trauma – while quietly – they are imploding.

This occurs, not only for those directly affected, but teens with a perceived threat of danger. In fact, for many teens, their imaginations (fuelled by sometimes unreliable social media reported trauma and constant stream of graphic images) can magnify the events to even greater levels of terror. Many parents, teachers, grandparents and carers become concerned about the emotional well-being of their children, and begin looking for advice on how to respond to questions from teens about recent upsetting events.

What are the signs that a young person might be struggling?

Look for a combination of some of the following:

- sleeping problems, including nightmares, struggling to fall asleep, waking up during the night (you may need to specifically ask about this).

- physical symptoms such as headaches, stomach aches or feeling ‘unwell’ in general.

- not wanting to go to school or attend usual activities (sports, family/social events, use of public transport etc.) This could come from a fear of leaving a family member should something happens while at school. Or fear of something happening on public transport, or in a specific setting.

- regressive behaviour.

- changes in behaviour with teachers, carers, siblings and parents – becoming more withdrawn, tearful, aggressive or irritable than usual.

- drop in performance at school.

In Conversation

The following ten tips are based upon Save the Children‘s years of experience (as well as other resources), and can be used as a guide for adults supporting young people who are not directly involved in the crisis (assistance for teens directly exposed to trauma is best sought from a professional). The relevancy of different tips will vary depending upon a child’s temperament, previous experience, age and where he or she lives.

Young people often ask the adults in their lives to explain what they have seen and to reassure them about what will happen next. The role of parents is still to ensure that their teen knows they are safe with you.

TEN tips on how to help teens process media reported trauma:

1. Turn off the news!

Watching television reports or scrolling through images on social media may overwhelm tweens and teens. Overexposure to coverage of the events affects adults as well. Encourage screen limits, for a time, for both you and your teens. Process the information as you need to, but do your best to starve your news feed of the detailed stories, and begin again to focus on hope. This is not to ignore the facts, but our brains struggle to be in a constant state of ‘alarm’.

2. Listen to your tweens carefully, before responding.

Get a clear picture of what it is that they understand and what is leading to their questions. Emotional stress results, in part, when a young person cannot give meaning to dangerous experiences. Find out what he or she understands about what has happened. Their knowledge will be determined by their age and their previous exposure to such events. Begin a dialog to help them gain a basic understanding that is appropriate for their age and respond to their underlying concerns (Hint – very often an underlying concern can be for personal safety or the safety of loved ones. Teens are also currently quite fearful about the future and the state of their earth).

3. Give reassurance and psychological first-aid.

Assure them about all that is being done to protect children, animals and those directly affected by the crisis. Take this opportunity to let them know that if any emergency or crisis should occur, your primary concern will be their safety. Make sure they know they are being protected. Have 2 or 3 main steps you can verbalise, to indicate this.

4. Expect the unexpected.

Not every tween or teen will experience these events in the same way. As young people develop, their intellectual, physical and emotional capacities change. Younger children will depend largely on their parents to interpret events, while tweens and teens will get information from a variety of sources – which may not be as reliable. Older teenagers, because of their greater capacity for understanding, may be more affected by stories. While teenagers seem to have more adult capacities to recover as well, they still need extra love, understanding and support to process these events. So be aware that, for some, their more general heightened emotion, moodiness or withdrawal may be a result of what they are trying to process (often they won’t even realise this).

5. Give your teen extra time and attention in age appropriate ways.

Parents, don’t underestimate the power of your own nurturing.Children and teens need your close, personal involvement to comprehend that they are safe and secure. Talk, kick a ball, journal, make a hot chocolate, offer a hug and, most importantly, listen to them. Find time to engage in special activities with your teen.

6. Be a model for your teen.

Young people will learn how to deal with these events by seeing how you deal with them. Base the amount of self-disclosure on the emotional and developmental level of each of your children. Explain your feelings but remember to do so calmly. Watch your own behavior. Make a point of showing sensitivity toward different countries, cultures and people affected by the disaster. This is an opportunity to teach your children that we are all part of one world and that we all need to support each other.

7. Help your teen return to normal activities.

Young people almost always benefit from activity, routine and sociability. Ensure that your child’s school environment is also returning to normal patterns and not spending great amounts of time discussing the crisis in unhelpful detail.

8. Encourage your teen to do volunteer work (where possible).

Helping others can give your teen a sense of control, security and empathy. Indeed, in the midst of crisis, adolescents and youth can emerge as active agents of positive change. Perhaps encourage your teen to help support local charities that assist children in need?

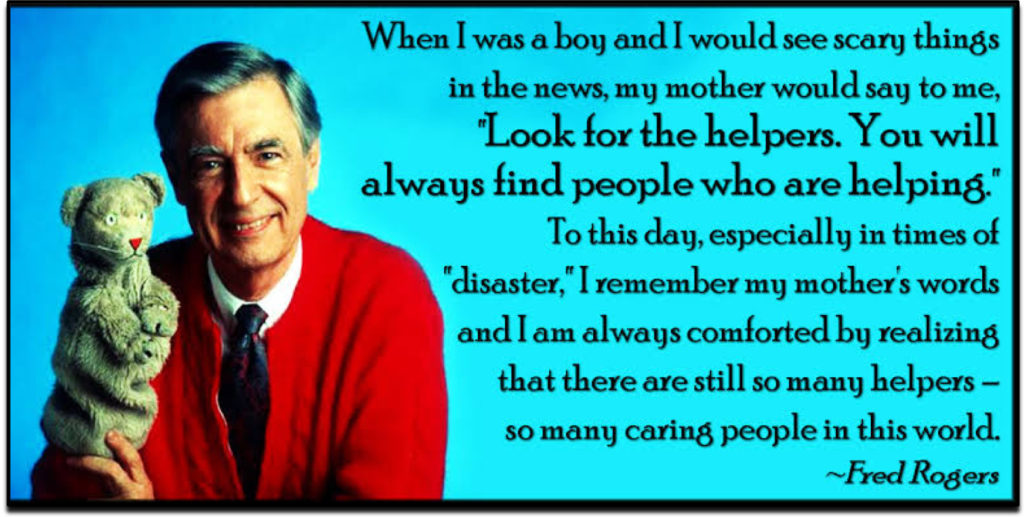

9. “Look for the helpers.”

Despite the mass media attention to trauma and chaos, we need to remain mindful that there are often only a few evildoers involved in reprehensible incidents. Even in the face of natural disasters, the list of people willing to do good goes on and on, growing by the minute. We see it every time – people lined up, ready to do anything to help. Point them out to your teens – the local neighbours bringing food and making donations, the kind bus driver comforting a grandma, the police officers, the fire fighters, the animal rescue workers, anyone else you notice…

10. Look out for teens with a history of anxiety or depression.

They can often be at increased risk, when they see bad news in the media, as the images they see and stories they hear, magnify their anxiety. These kids need a little extra patience and reassurance. Perhaps consider asking a school counsellor to chat with your child in the following weeks.

Last thoughts – Caring for survivors and their loved ones

For young people directly affected by this crisis (as well as those who have loved ones directly impacted in another area/city), parents should consider counselling. Not just for their teen, but also for the entire family.

Especially important to consider is that after a few weeks have gone by and the news moves on, onlookers tend to get on with their own lives and expect that those affected by the trauma, ‘Should be over it by now’. In fact, once the initial shock has passed and the reality has set in, it is at this time that nightmares, flashbacks and other symptoms of trauma can occur. This is the time to lean in and draw near.

Teachers and parents should be alert to any significant changes in eating habits, concentration, emotion/mood, sleeping patterns, sudden bed wetting, nightmares or frequent physical complaints without apparent illness. If present, these will likely subside within a short time, but without appropriate support and care they can become prolonged.

I strongly encourage you to seek psychological support and counselling.

Please support or encourage a parent, by sharing this article with them.

Other resources:

Save the Children Australia

Save the Children New Zealand

Save the Children Canada

Save the Children Asia

Save the Children Europe

Your local Psychological Society or GP will also have further information.

Wellbeing with Collett: Bad News Media & Talking with our Children

My name is Collett Smart. I am a psychologist, qualified teacher, speaker, podcaster and internationally published author, with more than 25 years experience working in private and public schools, as well as in private practice. I am married and have 3 children aged aged 22, 20 and 14 years-old.

Welcome to Raising Teens!

My name is Collett Smart. I am a psychologist, qualified teacher, speaker, podcaster and internationally published author, with more than 25 years experience working in private and public schools, as well as in private practice. I am married and have 3 children aged aged 22, 20 and 14 years-old.

Welcome to Raising Teens!